Ice Formation on Georgian Bay

In honour of the recent cold snap, we’ve dug up two “Georgian Bay Queries” from the archives of our LandScript newsletter, explaining the details of how ice forms on Georgian Bay.

In 1994 Georgian Bay froze completely over. Credit: Modis Real-time Satellite

Georgian Bay Query: How and when does ice formation happen on Georgian Bay?

Answered by Bill Lougheed, former Georgian Bay Land Trust Executive Director (originally published 2014)

When you curl up by the fireplace in the late fall, things are happening, especially at night, in the great outdoors. The few of you who have been lucky enough to observe the ice come or go on the shores of Georgian Bay have witnessed the spectacular natural process of which I speak.

In early December of most years, ice will first form in those small, protected, inland shallow marshes, bays and lakes. If one were to look from the air at the Georgian Bay coastline at this time using the near-real-time satellite (Modis: https://coastwatch.glerl.noaa.gov/satellite-data-products/modis/) one may actually watch the ice “come in” over several weeks as the inner lakes begin to freeze. Indeed, all of the inland areas with quiet water-bodies from Hwy 69 to the coast will now progressively form an ice cover and turn white as snow falls on them. Since water flow (or current) is an enemy of ice, rivers feeding the Bay remain open - warmer bottom water is continually stirred up in these systems and never forms thick/safe ice. Water depth is also an archenemy of ice so you will see that Lake Joseph, with its deep water, is the last of the Muskoka lakes to freeze in the early season.

The big Georgian Bay remains wide open at this time, its big thermal body yet to cool, snuggling up to its coastal bays and keeping them open (think maritime climate).

On Georgian Bay proper, the big freeze comes weeks to a month later. The first to succumb to winter’s onslaught are those small and shallow sheltered bays and coves. These areas will slowly expand and interconnect to form thin bands of “near shore ice” along most coastal stretches of the Bay (that are protected from wind and wave by outer guard islands). These areas will slowly expand further to form an ice band that by mid-winter extends 1-2 miles off the eastern shore. Conversely, unprotected areas not guarded by islands, for example, O’Donnell Point, will remain exposed and dangerous for the entire winter season.

The first major area of Georgian Bay to see large “sheet ice” coverage is the shallow area of Severn Sound (think Midland & Penetanguishine bays across to Beausoliel Island to Waubaushene). This usually happens in the first two weeks of January, but has occurred as late as February 1st. Most of the large bays of the north east shore of the North Channel will freeze in these first weeks of January where winter still sets in earlier and brings colder winter climes. A substantial ribbon of shore ice also takes its hold at this time on the more northerly coast from Key Harbour to Killarney.

In rare and exceptional years, Georgian Bay has frozen entirely over (twice in my memory), the latest being in 1994 (see image above).

Ice conditions can vary greatly from year to year. In a mild winter, the maximum ice coverage on Lake Huron and Georgian Bay may be as low as 26% (winter 2001-02) while during a severe winter the coverage can be more than 95%. Ice has formed as early as the last week of November and has persisted as late as the third week of May1.

In sheltered harbours and bays, lake ice typically grows to 45 - 75 cm during a normal winter. Areas of ridging out offshore on the Bay can contain ice thicknesses of up to 18 metres.

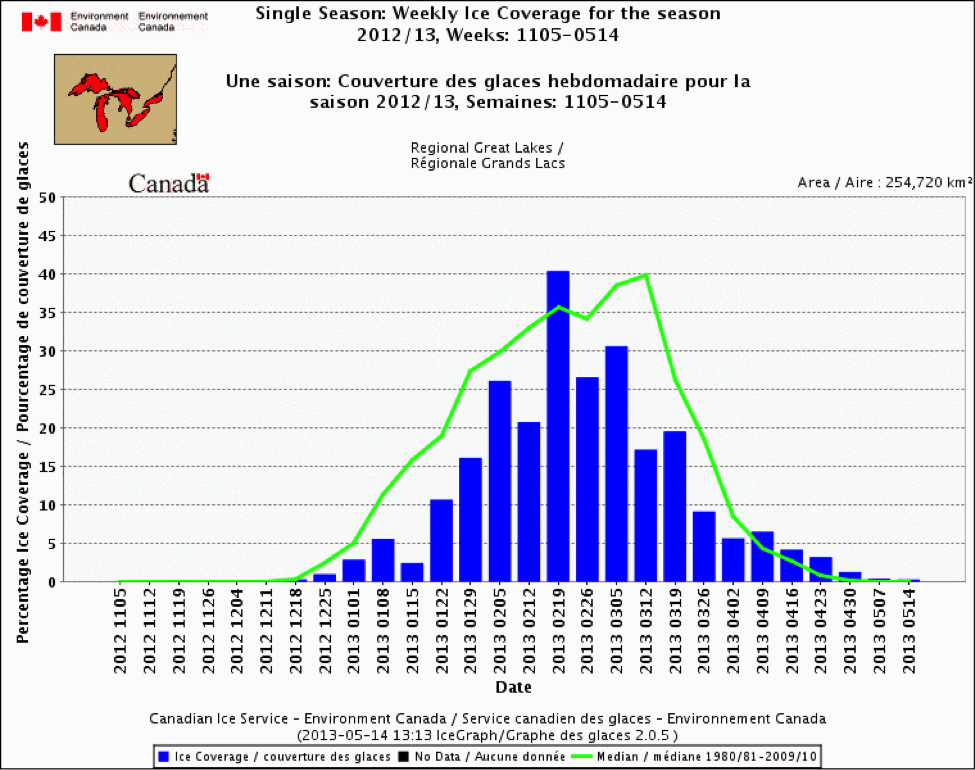

Average progression of ice cover on the Great Lakes. Credit: Environment Canada

Ice Physics

Ice can be black ice (it is crystalline with a columnar structure and so you can see through it), which is formed when heat is lost to the cold atmosphere from the water underneath the ice. Per inch, “black ice” is much stronger and safer than other forms. Four inches (10 cm) of black ice will support a team of horses.

Ice can also be snow ice (it is a disordered structure so you cannot see through it), which occurs when the ice layer is submerged by heavy snow and water subsequently freezes in the slush layer.

Ice on a small lake is formed rather quickly after the surface water is cooled down to the freezing point – most often after a cold night with no wind. Two concurrent still nights of -20°C can form 3-4 inches of ice. Large lakes require much longer to freeze over, since relatively warm water is brought to the surface during the more intense mixing in a large lake.

Interestingly, water is a weird molecule. It is most dense at around 4oC but gets lighter below this temperature. Because ice on a lake is less dense than underlying water, it floats. Without this unique property, life on Earth would probably not exist. Without it, surface ice would form; sink to the bottom; more surface ice would form and sink etc. Quite quickly the lake would freeze to the bottom, killing all aquatic species present!

The History of Ice

Today, scientists use ice cores from Greenland and Antarctica to determine world temperatures dating back over 100,000 years using rations of two types of oxygen that occur within ice.

Calendar dates of freezing and thawing of lakes has been recorded in writings for hundreds of years. These records existed before the invention of modern thermometers. For example, Lake Suwa in Japan has an ice record dating back more than 550 years. Often, these early ice measurements were made for religious, cultural, or practical reasons concerning transportation over ice vs. open water. Scientists can use these records to estimate past climate and weather conditions, using lakes as sentinels of broader climate change.

What Factors Make Ice Thin and Dangerous

Narrow waterways – water will flow here

Narrow gaps between islands

Beaver ponds – the beavers make channels and you can break through even in the depth of winter

Marshes in March – bogs heat up due to bacterial processes.

In the spring, near-shore areas where the land is warm and will heat the ice

All rivers

Big open areas where wave action occurs

All areas on GB not protected by outer guard-islands

All big open stretches where waves can build

Points - wind and water are forced to sweep around these areas

You need local knowledge to travel on the ice in winter. If you don’t have this knowledge, go with a friend who has it or stay by the fire where this story began.

Georgian Bay Query: How is lake ice changing and what does that mean for the Georgian Bay ecosystem and us?

Answered by James Rusak, Adjunct Professor, Department of Biology, Queen’s University (originally published 2023)

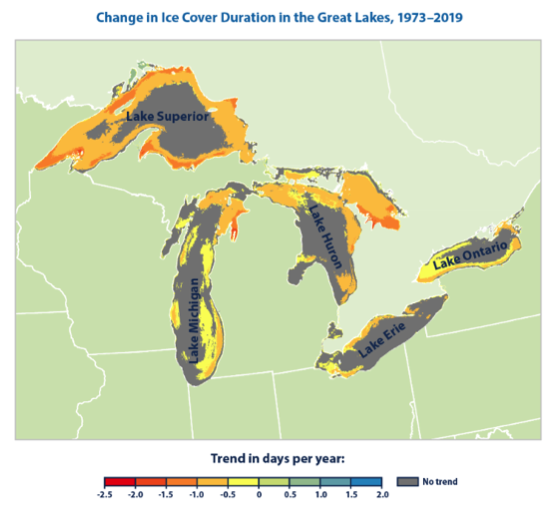

Both locally and globally across the Northern Hemisphere, the length of ice cover is becoming shorter and shorter. The Great Lakes region is no different and Georgian Bay is one of the areas currently undergoing some of the largest changes (see map below). Depending on where you are in the offshore areas of the bay, this reduction in ice cover is on the order of 20 - 40 days since the early 1970’s. These changes in ice cover are directly linked to warmer air temperatures resulting from human-induced increases in greenhouse gas concentrations that have resulted in a changing climate. Although this may allow for an earlier cottage opening and later closing for many, there are numerous other less desirable outcomes of these losses of ice cover for the Georgian Bay ecosystem.

This map shows the average annual rate of change in the duration of ice cover in the Great Lakes from 1973 to 2019. Duration is measured as the number of days in which each pixel on the map was at least 10 percent covered by ice. Gray areas are labeled “no trend” because the change over time is not statistically significant (using a 90-percent confidence level). From: NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). 2019. Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory: Historical ice cover.

The impacts of reduced ice duration can be both direct and indirect. Ice cover can protect incubating eggs (e.g., lake trout, lake whitefish) by lessening wave action on shallow spawning shoals. Further, once small fish do hatch, reductions in ice cover can affect how quickly a lake warms and therefore the timing of the zooplankton (food for young fish) production. Reductions in ice coverage can also have impacts on water temperature that carry over to subsequent seasons, leading to unseasonably warmer temperatures in the summer and fall. Longer growing seasons typically support the production of blue-green algae which can form toxic algal blooms, harming fish, aquatics habitats, and water quality alike. Less ice cover can also result in greater evaporation from the lake surface, which in turn can lead to greater variability in lake levels over the long-term and increases in snow and rain in areas adjacent to the Bay. In southern Georgian Bay, greater snowfall (and earlier rain events) can wash nutrients off agricultural lands before they can be taken up by crops, providing additional potential for harmful algal blooms later in the ice-free season.

Ice safety is directly related to ice thickness and warmer winters typically lead to reductions in ice thickness that can result in unsafe ice conditions relative to cooler winters. In fact, increased winter drownings are known to occur in ice-covered regions during warmer winters. Warmer winters can also affect the quality of lake ice. We usually learn that it is okay to walk on ice if the ice thickness is 10 cm or more. However, 10 cm of ice holds up to 1,753 kg under clear or “black” ice conditions, but under certain white ice conditions ice strength can be an order of magnitude less. Because the strength of white ice is so low, an increase in the proportion of white ice can jeopardize the use of seasonally ice-covered lakes for subsistence, recreation, transportation and other purposes. White ice is commonly formed when snow accumulates on ice, melts, and refreezes or when rain falls on the snow layer to form slush that subsequently freezes. Warmer winter air temperature can increase the number of days with air temperatures near the freezing point, thus increasing the proportion of white ice. Ice conditions that traditionally have been safe during winters of the past will become unsafe in the future and there is an urgent need to consider this change in ice quality to ensure safe travel on ice. White ice also has implications for the ecosystem too as its only allows small amounts of light to penetrate. Low light conditions in spring caused by a white ice layer and/or snow on ice may change the base of the food web with consequences that could potentially cascade throughout, with substantial consequences for zooplankton and fish populations.

Changing ice duration and ice quality have the potential to change many aspects of the Bay and how we come to enjoy all it has to offer. Doing what we can to slow the rate of climate change can be an important part of what we can do to mitigate these effects.